Kids Fighting For Kids – a new ‘Dig Where You Are’ story

In Costa Rica, a young surfer has turned his love of Jiu Jitsu into a transforming experience for kids at risk.

“I always tell the kids here that nothing is impossible. The ‘impossible’ things just take longer to do,” says Leonidas (Leo) Ruaro, the twenty-nine-year-old surfer who created the Brazilian Jiu Jitsu Jaco Academy (BJJJ) in Costa Rica. “Don’t be afraid to start, I say. I think people talk a lot about doing stuff. They should just stop talking and do more.”

Through a row of plate glass windows is BJJJ. It is home to 80 kids, most under the age of 13, and some who would already be involved in drugs and crime if they were not involved here. The walls inside are white-washed and a hand painted yin/yang or Taijitu symbol dominates one side of the room.

Even the setting sun doesn’t bring relief from the heat here. As the day fades, groups of children trickle down the dusty alleyway behind the overflowing dumpster. The once empty warehouse is set back off the main road behind a gas service station. Without a hand drawn map, it would be impossible to find.

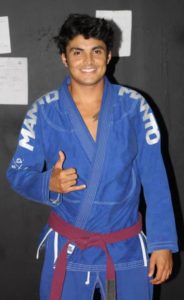

Leo is preparing for the evening’s class. Barefoot and dressed in his gi (a thick white cotton jacket and pants) he moves quickly around the room. Ten years ago, after training in Tae Kwan Do, he began learning Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Today he is a brown belt, the highest ranking color in the sport.

“In Jiu Jitsu you really have to think,” he says shaking a damp curl of black hair off his forehead. “It’s like human chess.”

The sport originated from Japanese Judo. Rather than meeting an opponent with a kick or a punch as in other martial arts, Jiu Jitsu is a sport where strength is trumped by skill. It is a martial art that you cannot learn alone. You must have a partner.

“And that is why it works with these kids,” he says as he notes the arrival of another group of students. “Each has to teach what he learns.”

Several years ago Leo started teaching a couple of boys – the children of friends.

“When the group got to be more than five, I asked each to bring another kid with them to class.” The numbers grew quickly. Although not all, most come here from broken homes. Some live in the slums, some are the kids of drug dealers and prostitutes. Others come from families that are rife with abuse.

Costa Rica for the most part is a success story and anyone visiting this oasis in the middle of conflict-ridden Central America can’t help but be struck by how well things work. While the gap between rich and poor in Costa Rica is not as extreme as that of its neighbors, there are slums and shanty towns, and a growing underbelly. The resort town of Jaco with a population of 10,000 caters to the tourist trade. Along with cheap restaurants and surf shops however Jaco is also plagued with the seedy side of tourism: drugs, thievery, prostitution and sex trafficking.

Not all the kids who come to BJJJ Academy are at risk of being pulled into this life, but enough are and Leo knows it.

A large metal corrugated door, which is kept locked during the day, has been raised to let the children in. Two girls, no older than nine, push through the opening and past a group of boys who stand a head taller than they. The Academy accepts both boys and girls.

“Sometimes we get boys who don’t want to fight girls. They don’t think girls are good enough,” says Leo. “One time I bet one of those boys that if he could tap out a girl I would give him my gi, my belt and my car. He accepted the challenge. I told the girl not to go easy. I told her to kick his ass. And she tapped him out 6 or 7 times. At the end of that fight I stopped the class and called the girls to the front and I said to everyone: girls and boys are the same, the only difference in how we pee.”

Leo has two rules by which everyone who comes here must abide. First, in exchange for learning Jiu Jitsu for free, each child is expected to pay back by introducing two others to the sport. The second rule is that everyone must maintain good grades. If you don’t keep good grades, you are suspended from the Academy for a month. Just understanding the consequence keeps the kids in good academic standing.

There are other rules regarding hygiene, arriving on time, practicing consistently, listening, treating others with respect and helping out.

Leo grew up in a community just south of Jaco. In university he studied Hotel Management. “I could have worked in a hotel and made more money. But then I wouldn’t have time for the kids,” he says. “Instead I teach surfing. And I’m a rep for a U.S. clothing company.” Since Leo doesn’t charge for lessons he draws on his own income to pay expenses. These include taxi costs for kids who live in villages too far to walk from, food for those who come hungry, a birthday cake for someone who has never celebrated a birthday, and the gis. He prefers not to take cash donations. He doesn’t want to manage the money. But he does take donations in-kind like school supplies for those whose families cannot afford them and gis, and he actively recruits these.

Among the challenges that Leo confronts in addition to operating with limited resources, or dealing with difficult kids, are the parents and adults in these children’s lives.

“One day, one of the boys came to class without his gi and I said: where’s your uniform? The kid said – oh my stepfather burned it. And I asked why. He told me that his stepfather was beating his mom and he pointed a gun at her and said he was going to kill her. When the kid told his stepfather to stop, the man grabbed all the kids’ clothes and school supplies and burned them. This kid was 8 years old and his younger brother was 7 and they both came to the Academy. When I heard this story I just cried. Then I called a friend who works in social work. He told me that the only way you can end this is to kill the guy. Because if you call the police then the police will take the kids away and put them in a foster house and that will be much worse. And if you tell the mom to leave the guy, then she will leave him and then they will get back together. And if you go and beat the guy up then he will beat the kids, or kill the kids or kill the mom or kill me. It’s situations like this that have been the hardest for me.” Leo sighs and shakes his head.

The commotion in the room is mounting as more kids arrive. Large fans blow in a futile attempt to cool the space. The young bodies covered in sweat show no fatigue. Another instructor has arrived. He is Arturo, Leo’s right hand and a good friend. Shoes and sandals are scattered across the only bare piece of concrete floor. The rest of the space is covered with a white rubber mat. Leo and his friends made the mat themselves from a pile of shredded rubber tires and a large tarp stretched over top. The mat looks brand new.

Leo stands beneath the Taijitu symbol. Within seconds everyone is seated cross legged facing him. Leo and Arturo demonstrate a choke-hold explaining each movement in detail. Then two of the older boys scoot forward and show what they just learned. The rest follow, covering the white mat with twisting bodies, a collection of legs and arms; flexed toes and feet hooked across backs, heads buried in arm pits; pinned shoulders; mouths ajar, eyes squeezed shut, brows furrowed in concentration.

Every night Leo teaches the kids and after, he teaches adults. He charges the adults the equivalent of $28/month which helps to finance the taxis for the kids. He is trying to set up a foundation so that he can receive government support and maybe enough money for a van.

The BJJJ Academy changes the kids who come here. No matter where you are from, once you get on the mat you are only what you do.

“I see change all the time,” says Leo. “In Jiu Jitsu you have to listen, learn and practice or you’ll get beat up. It’s like real life. Here kids learn that life can be different. They learn that they are in charge of themselves. I don’t have to force that. And every day I see a kid grow up and a life changed.”![]()

If you want more information about BJJJ visit the Brazilian Jiu Jitsu Jaco Facebook Page If you want to be in touch, send an email to Leo at bjjjaco@gmail.com and ask him what he needs.