The Healing Power of Art

While working on ‘Dig Where You Are’, I had a conversation with Lily Yeh about her experience in Rwanda. She recounted for me how art and the process of creating something collectively helped a village of genocide survivors to heal and rebuild their lives.

“When you go to Rwanda for the first time you must experience the Genocide,” said Lily.

“When you go to Rwanda for the first time you must experience the Genocide,” said Lily.

She pushed her computer closer so I could see a photograph of the interior of a church where in the summer of 1994, thousands of Tutsis were locked inside while grenades were dropped through the open windows.

The pastor of the church had facilitated it.

Another photo showed where thousands more had been assassinated. The walls, still standing, were peppered with bullet holes. The pews were gone; the pulpit untouched. Then a dim room where earthen skulls, femurs, shoulders and ribs had been thrown. Lily pointed to a split in one of the skulls – a machete strike. Clothing, once belonging to mothers, fathers and children, lay in piles, the colors drained. A shirt hung on a hook on a post. I wondered who had made the effort.

“My desire to hear people’s stories comes from pictures like this one. It is what is buried there, “said Lily.

For over three decades Lily has been listening to stories told by those who for the most part the rest of the world has forgotten. Beginning with a small project in North Philadelphia in the early 1980s where she engaged gang members, drug dealers and their families in helping to create a sculpture park and then transform a whole neighborhood, she learned firsthand how art and the creative process can help people to heal.

“Art disarms people,” she said. “Behind the veils of joy and healing is a non-confrontational, nonviolent and non-militant way. It is like the way of the water. You go to lonely places and you slowly let the moisture be absorbed, slowly the environment changes. You make a shift in awareness and the awareness is about being valued.”

In 2004, a decade after the Rwandan Genocide Lily Yeh met Jean Bosco Musana Rukirande, a regional director for the Red Cross in Gisenyi and a survivor. Before, he had been a professor of Biology and Chemistry. When Lily encountered him, he was working to rebuild his country and the broken lives of his countrymen. His account so moved Lily that when he invited her to visit Rwanda she accepted.

In the western region of Rwanda is Rugerero Village. The people there once lived in the neighboring communities in Gisenyi, Cyanzarwe and Kibuye. Now they live together in brick structures provided by the government. Most did not know each other before the genocide. Now they are neighbors forced to find a future together. When Lily arrived they were sharing houses, but had nothing else. Their homes were gone, their loved ones murdered. Some were the only remaining members of large multi-generational families. Before the genocide they were plumbers, teachers, cooks, mothers and fathers. Afterward, they were just survivors.

Jean Bosco showed Lily the mass grave outside the village which had been built in haste for the remains of the genocide victims. It was a crude concrete structure which encased a cement casket of bones. Over the opening was a bent metal roof which leaked when it rained pouring water into the grave.

The villagers told Lily that each time they passed it they felt as if they were being killed over and over again. More difficult than dying was surviving.

“I felt the loss in their bodies, in their faces, and then the sense of despair” said Lily as she reflected on her first encounter with the people of Rugerero.

Jean Bosco knew how Lily had used art to help rebuild a decimated community in North Philadelphia and then a slum outside Nairobi, Kenya. He also knew that the people of Rugerero needed a proper memorial to their dead before they could move forward. If they could see beauty again, they might find hope; and Lily was the person to help them.

Lily knew from experience that before the villagers had a chance at rebuilding their lives, they had to put back together their fractured and fragmented souls and hearts. They had to mourn their loved ones properly. Most Rwandans are Roman Catholic and believe in the soul finding its final resting place with God. Lily understood that only after the living had made peace with the past, would they have the capacity to create a future for themselves.

So she got to work. “I first made a sketch of the memorial plot I wanted to create. Then I got the China Road and Bridge Company [which was working in Africa at the time] to help me. So we dug down and created a bone chamber. Then the villagers gave me words and we made mosaics on the memorial with these words. They painted the undulating walls around the exterior that enclosed the memorial– white, purple and the colors of Rwanda’s flag. They chose the color purple because it is also the color of mourning.”

The making of art together created the space for people to talk to each other about the terrible things they shared. “They put their stories on the urns and the urns were filled with plants and herbs and medicine so they could grow and be a living museum,” Lily said. The urns were placed at the Genocide Memorial Park and when it was all complete, there was a ceremony.

“The villagers decided what to wear, what to sing, what to dance, what to say at the memorial ceremony. The place was sanctified and the seeds sown and they carried the urns and remembered. You do not only remember individually but also collectively. That is how you mend the broken pieces, you remember as a whole.”

In the beginning the Rwanda Healing Project, as Lily called it, had two parts. The first was to properly bury and honor the dead in a new Genocide Memorial Park. The second was to transform the survivors’ village, convert the ugly grey buildings to colorful illustrations of hope and life, so that every day they would be reminded of the beauty and possibilities of life ahead.

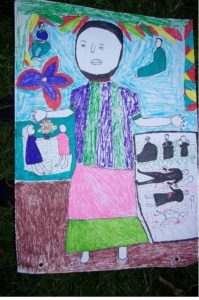

“I brought volunteers [from the U.S.] and the children painted. It turned into public art. The images are very Rwandan. There is a cow,” she said pointing to photograph of a large mural on the side of a hut. “I made the utter very big. Then we trained them how to paint and they continued to paint after I left and they painted their dreams.”

“What is this?” I asked pointing to a photograph of carved figure of a man with two heads. The wood was pale, almost white and the expression on the faces of each head had been carefully culled out of the soft material. One face was looking up as if asking God why this had happened to them, the other looked down his eyes soft with compassion.

“What is this?” I asked pointing to a photograph of carved figure of a man with two heads. The wood was pale, almost white and the expression on the faces of each head had been carefully culled out of the soft material. One face was looking up as if asking God why this had happened to them, the other looked down his eyes soft with compassion.

She explained that this had been part of a later project to beautify the local school.

“We got the children involved in painting,” she said. Then she asked a man to make a sculpture out of wood. “I just made a sketch and this is what he came back with,” she said. “He too was surprised by his own ability.”

The Rwandan Healing Project spanned several years during which Lily came and went from her home in the U.S. One year she hired an engineer to teach the villagers how to build a cistern to capture rain water for drinking. Another time she brought a solar engineer to help the villagers build solar panels to generate electricity to power light in homes and in a sewing workshop. Lily created a small micro-financing fund with $2,000 she raised. The villagers have taken loans to start small businesses including making dolls, sunflower oil and banana leaf charcoal.

The Rwandan Healing Project spanned several years during which Lily came and went from her home in the U.S. One year she hired an engineer to teach the villagers how to build a cistern to capture rain water for drinking. Another time she brought a solar engineer to help the villagers build solar panels to generate electricity to power light in homes and in a sewing workshop. Lily created a small micro-financing fund with $2,000 she raised. The villagers have taken loans to start small businesses including making dolls, sunflower oil and banana leaf charcoal.

Lily sees her work in Rwanda as Yin and Yang or that which has to do with the Genocide and that which has to do with life after the Genocide. Some of her work addresses the past, such as the memorial and tomb; the rest looks to the future and the lives of the people who have survived. She evokes the idea of Shiva – the creator and the destroyer – as the embodiment of what she has experienced here and in so many other places in the world.

“Do you ever wonder why some experience such horror in life while the rest of us are spared?” I asked.

“That is the question I ask when I go to places of such deep suffering and find such joy. I don’t have the answer. But I feel that in broken places the depth of humanity is revealed,” Lily said. “It is in these broken places when we see who we are.”

![]()

Photographs are courtesy of Lily Yeh and Barefoot Artists

Resources

View the Rwandan Healing Project – a movie about Lily Yeh in Rwanda

Dallaire, Romeo. Shake Hands with the Devil – The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003

Gourevitch, Philip. We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998.

Gourevitch, Philip. Remembering in Rwanda. The New Yorker, April 21, 2014

Ilibagiza, ImmaculeÌe, and Steve Erwin. Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust. Australia: Hay House, 2006